Hay momentos en el mundo en los que necesitamos estar dispuestos a sentirnos perturbados. A no apartar la mirada de aquello que nos asusta y que nos deja clara nuestra finitud e impotencia como seres humanos. ¿Es en el espasmo de la perturbación donde encontraremos la fuerza para transmutar la realidad de nuestros cuerpos condenados? ¿Qué potencial transformador ofrece la estética de lo siniestro? ¿Qué está en juego cuando se suprime lo sublime? Las sociedades contemporáneas están impregnadas de una anestesia sistemática, lo que conduce a la proliferación de prácticas artísticas que movilizan una belleza optimista e inofensiva. Esto nos condiciona a un nihilismo que se niega a enfrentarse o a dejarse afectar por el poder estético (ético) de la carne y la sangre temblorosas de los mártires.

Tengo la teoría de que hemos encarnado este entumecimiento sensorial desde aquellos tiempos en que la mirada domesticaba la flora y la fauna a través de la pintura, una disciplina promovida por las colonias que se extendieron brutalmente por todo el mundo. La relación recíproca y constitutiva entre la belleza y el horror tiene su origen en la pintura paisajística, la pintura etnográfica y los bodegones. Esta relación fue desencadenada por el saqueo colonial, un sistema que incluía la extracción, la explotación y la comercialización de flores que decoraban millones de hogares europeos. Desde el siglo XVI, los bodegones en particular —una de las tradiciones pictóricas más antiguas del arte occidental— han convertido la decadencia de las flores en un símbolo de belleza. Esto estableció a las flores como el centro de la percepción y la encarnación misma de la belleza en tensión con la muerte, en un momento en que el protestantismo eliminó el arte de la divinidad religiosa como tema de su imaginería. En consecuencia, la representación de las flores en descomposición confinó la idea de la belleza al placer sensual e inmediato, a los objetos agradables a los sentidos, a la moderación en las proporciones, a la contemplación pacífica y a las emociones serenas. Es en el motivo de las flores donde se sustenta una idea clave de lo que acabó convirtiéndose en la piedra angular de la colonialidad: la universalidad. Con cualidades como la claridad del tono, la luminosidad de la superficie y la suavidad y variedad de colores, la belleza a través de la pintura llegó a suspender la descomposición de la flor arrancada que muere sumergida en el agua de un jarrón. Una instrumentalización de la estética de la relación recíproca entre la belleza y el horror, velada por la técnica pictórica para establecer una sensibilidad moral incapaz de reconocer el horror que la sustenta y la motiva.

Ante la insistencia colonial histórica de elevar las flores como símbolos de bondad moral, Javier Barrios (Guadalajara, México, 1989) transmuta a través de sus dibujos su representación —y el significado mismo de la belleza— en horror cósmico. Este horror nos confronta con la grandeza de algo tan vasto y antiguo que resulta casi incomprensible. Los dibujos de Barrios nos invitan a interpretar escenas que rompen no solo con las coordenadas habituales de la realidad, sino también con la imaginación bajo regímenes monoculturales. Apropiante de la estética de la ilustración botánica y animal, y rindiendo homenaje tanto a las formas artísticas zapotecas como al dibujo japonés y chino, Barrios retuerce la representación occidental de las flores para retratarlas como imponentes deidades monstruosas y habitantes de un cosmos infernal. Estas deidades se revelan como entidades extrañas, temibles y omnipotentes que parecen contener el caos primordial donde la fuerza vital de la existencia se revoluciona continuamente.

Como ángeles exterminadores, las orquídeas de Barrios —inspiradas en aquellas que atraen a polinizadores malolientes— nos miran fijamente con ojos de araña y nos sonríen con colmillos babosos. Sus pétalos nos seducen con sus patrones de piel reptiliana, las texturas de su pelaje y sus venas afiladas, para sumergirnos en sus húmedos órganos sexuales, pliegues sugerentes expuestos como vísceras cuyos jugos dan lugar a la sodomía. Como ángeles exterminadores, las orquídeas de Barrios —inspiradas en aquellas que atraen a polinizadores malolientes— nos miran fijamente con ojos de araña y nos sonríen con colmillos babosos. Sus pétalos nos seducen con sus patrones de piel reptiliana, las texturas de su pelaje y sus venas afiladas, para sumergirnos en sus húmedos órganos sexuales, pliegues sugerentes expuestos como vísceras cuyos jugos dan lugar a la sodomía. Suspendidos en el aire, estos ángeles parecen descender, abriendo sus bulbos para revelar un aura que atrae con su misterio y horroriza con su exceso desgarrador, dándonos la oportunidad de alcanzar una visión ardiente de la «vida abierta». ¿Podría ser esta una oportunidad para abrazar lo imponente y fracturar cualquier presunción de supremacía humana?

A medio camino entre seres extraterrestres y deidades, habitantes a la vez de la Tierra y del universo, estas flores han desatado las llamas del inframundo para recuperar el control del caos que constituye el planeta, poniendo así en perspectiva cualquier presunción de poder entre nuestras sociedades humanas y mortales. Los dibujos anómalos de Barrios recuerdan el poder de las mitologías que expresan la ambivalencia del mundo, despertando así un doble sentimiento: curiosidad y asombro ante el misterio ilimitado que ofrecen, y horror ante la falta de puntos de apoyo, situándonos ante un horror indescifrable que motivará nuestras pasiones para escapar de la razón y la cordura civilizatoria. Solo los sabios escribas, cuyas moléculas ocultan el ciclo eterno de la muerte como una proliferación de vida, se han permitido perturbarse hasta el punto de la desposesión para experimentar el secreto deleite del terror y alcanzar lo extraño, lo indefinido y lo inefable. La invitación es a mirar al abismo, un choque necesario que nos hará abandonar toda certeza y enfrentarnos a la sublime posibilidad del horror.

– Diego Del Valle Rios

There are moments in the world when we need a willingness to be disturbed. To not avert our gaze from that which frightens us and which makes clear our finitude and powerlessness as human beings. Is it in the cramp of disturbance that we will find the strength to transmute the reality of our condemned bodies? What transformative potential do the aesthetics of the sinister offer? What is at stake when the sublime is suppressed? Contemporary societies are permeated by systematic anaesthetisation, leading to the proliferation of artistic practices that mobilise optimistic, harmless beauty. This conditions us to a nihilism that refuses to confront or be affected by the aesth(ethic) power of the trembling flesh and blood of the martyred.

I have a theory that we have embodied this sensory numbness since those times when the gaze domesticated flora and fauna through painting, a discipline promoted by the colonies that brutally spread throughout the world. The reciprocal and constitutive relationship between beauty and horror originates in landscape painting, ethnographic painting and still lifes. This relationship was triggered by colonial plundering, a system that included the extraction, exploitation and commercialisation of flowers that decorated millions of European homes. Since the 16th century, still lifes in particular—one of the oldest pictorial traditions in Western art—have turned the decay of flowers into a symbol of beauty. This established flowers as the centre of perception and the very embodiment of beauty in tension with death, at a time when Protestantism removed art from religious divinity as the subject of its imagery. Consequently, the representation of decaying flowers confined the idea of beauty to sensual and immediate pleasure, to objects pleasing to the senses, to moderation in proportions, to peaceful contemplation, and to serene emotions. It is in the motif of flowers that a key idea of what eventually became a cornerstone of coloniality is sustained: universality. With qualities such as clarity of hue, luminosity of surface, and softness and variety of colours, beauty through painting came to suspend the rotting of the plucked flower that dies submerged in the water of a vase. An instrumentalisation from the aesthetics of the reciprocal relationship between beauty and horror, veiled by pictorial technique to establish a moral sensibility that is incapable of recognising the horror that sustains and motivates it.

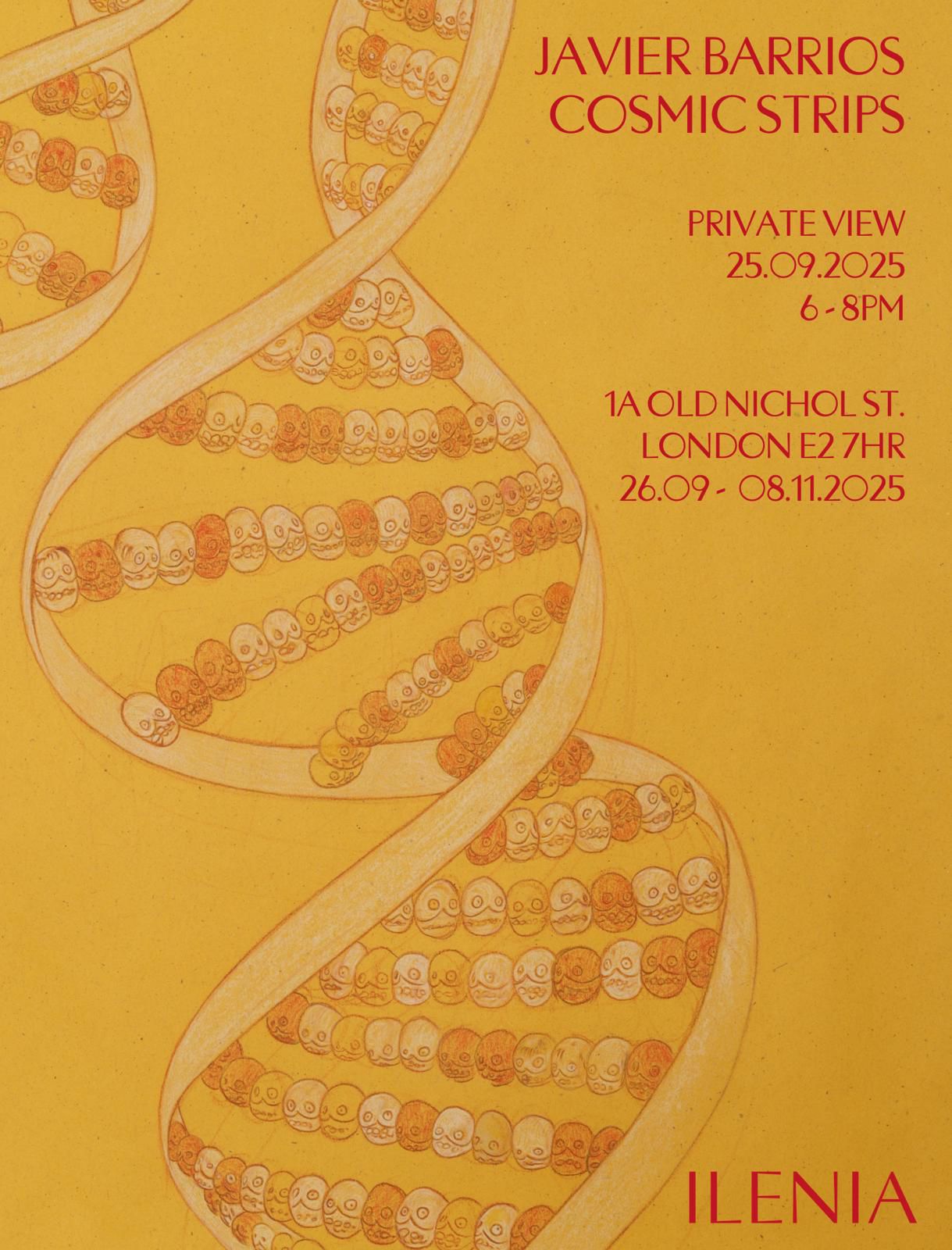

Faced with the historical colonial insistence on elevating flowers as symbols of moral goodness, Javier Barrios (Guadalajara, Mexico, 1989) through his drawings transmutes their representation—and the very meaning of beauty—into cosmic horror. This horror confronts us with the grandeur of something so vast and ancient that it is almost incomprehensible. Barrios’ drawings invite us to interpret scenes that break not only with the usual coordinates of reality, but also with imagination under monocultural regimes. Appropriating the aesthetics of botanical and animal illustration, and paying homage to both Zapotec art forms and Japanese and Chinese drawing, Barrios twists the Western representation of flowers to portray them as imposing monstrous deities and inhabitants of an infernal cosmos. These deities reveal themselves as strange, fearsome and omnipotent entities that seem to contain the primordial chaos where the vital force of existence is continually revolutionised.

Like exterminating angels, Barrios’ orchids—inspired by those that attract foul-smelling pollinators—stare at us with spidery eyes and smile at us with drooling fangs. Their petals seduce us with their reptilian skin patterns, the textures of their fur and sharp veins, to immerse us in their moist sexual organs, suggestive folds exposed like viscera whose juices give rise to sodomy. Like exterminating angels, Barrios’ orchids—inspired by those that attract foul-smelling pollinators—stare at us with spidery eyes and smile at us with drooling fangs. Their petals seduce us with their reptilian skin patterns, the textures of their fur and sharp veins, to immerse us in their moist sexual organs, suggestive folds exposed like viscera whose juices give rise to sodomy. Suspended in the air, these angels seem to descend, opening their bulbs to reveal an aura that attracts with its mystery and horrifies with its cracking excess, giving us the opportunity to achieve a burning vision of “open life”. Could this be an opportunity to embrace the imposing, and fracture any presumption of human supremacy?

Halfway between extraterrestrial beings and deities, at once inhabitants of Earth and the universe, these flowers have unleashed the flames of the underworld to regain control of the chaos that constitutes the planet—thereby putting into perspective any presumption of power among our human and mortal societies. Barrios’ anomalous drawings recall the power of mythologies that express the ambivalence of the world, thus arousing a double feeling: curiosity and wonder at the unlimited mystery they offer, and horror at the lack of footholds, placing us before an indecipherable horror that will motivate our passions to escape reason and civilisational sanity. Only the wise scribes, whose molecules conceal the eternal cycle of death as a proliferation of life, have allowed themselves to be disturbed to the point of dispossession in order to experience the secret delight of terror and reach the strange, the undefined and the ineffable. The invitation is to gaze into the abyss — a necessary shock that will make us abandon all certainty and confront the sublime possibility of horror.

– Diego Del Valle Rios