After the fall of their cult the gods took demonic shapes.*

History always appears scrambled — that is its natural form. The desire to hierarchize and organize it as a succession of facts, as simple cause and effect, was part of the dream of reason which, as we well know, only ended up producing monsters. It is at this crossroad, in that monstrous mélange, that the work of José Luis Sánchez Rull emerges. And in this exhibition it appears from the end — which is also a beginning, and vice versa. This double spatial-temporal positioning, almost contradictory, is more like a rebound or mirroring game that breaks apart the easy metaphor that art is a reflection of society.

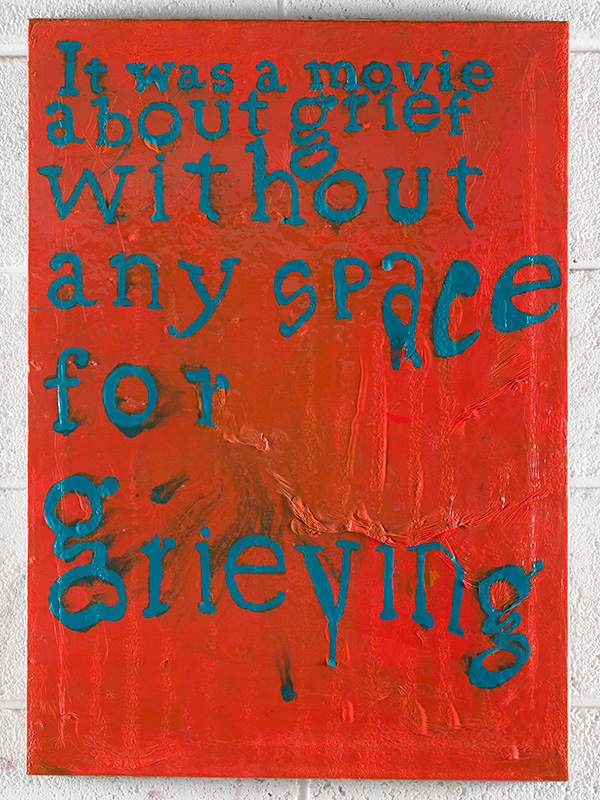

The only thing that interests us in that metaphor is the warning that appears on a car’s side mirror: “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear,” or the distorted reflection of a carnival’s mirror maze that returns to us our own image, ridiculous and mocking. Art must not reflect, but distort: that transformation is its prophetic nature. Art is not an illusory image; it is the space between the work and the spectator — a space that announces and attempts to warn that the disastrous collision is closer than we think and, therefore, might also bring our salvation.

The doubling I speak of is a kind of déjà vu; what has happened happens again, but with the dazed awareness that it has already been lived. That is where its moment of strangeness lies. “The uncanny is a somewhat muted sense of horror: horror tinged with confusion. It produces “goose bumps” and is “spine tingling”. It also seems related to déjà vu, the feeling of having experienced something before, the particulars of that previous experience being unrecallable, except as an atmosphere that was “creepy” or “weird”.” (Mike Kelley, Playing with Dead Things: On the Uncanny, 1993).

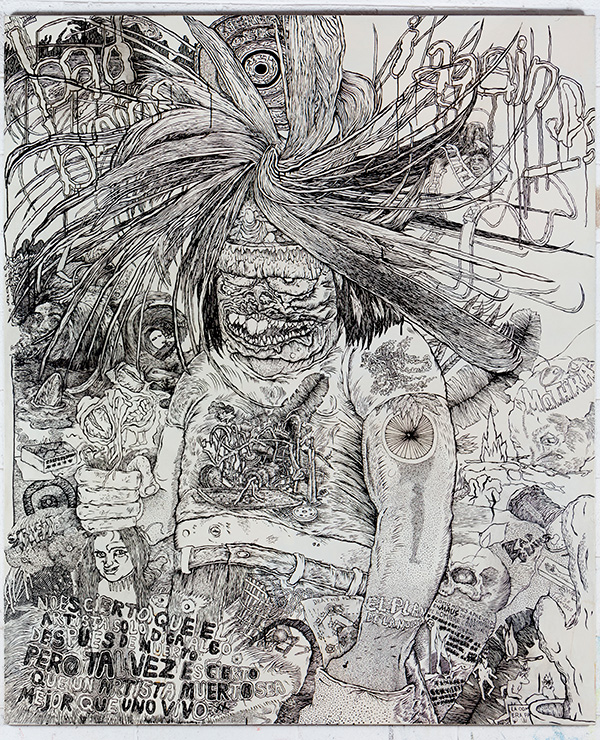

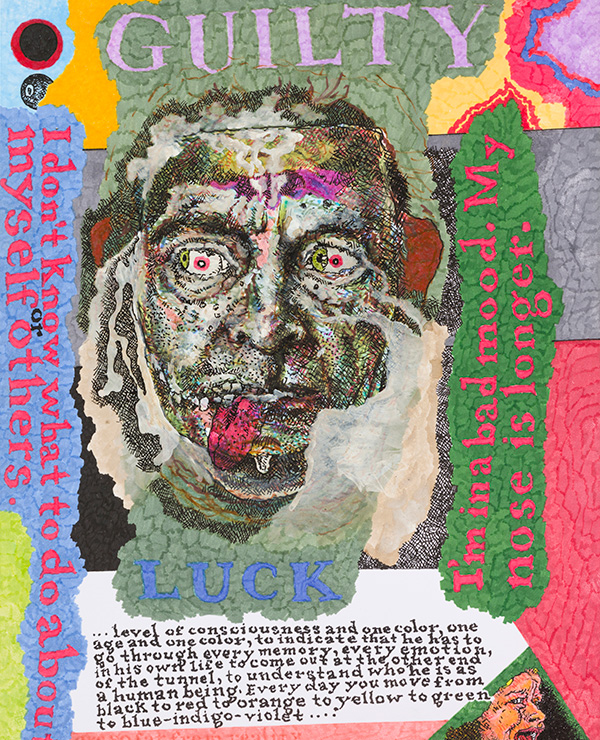

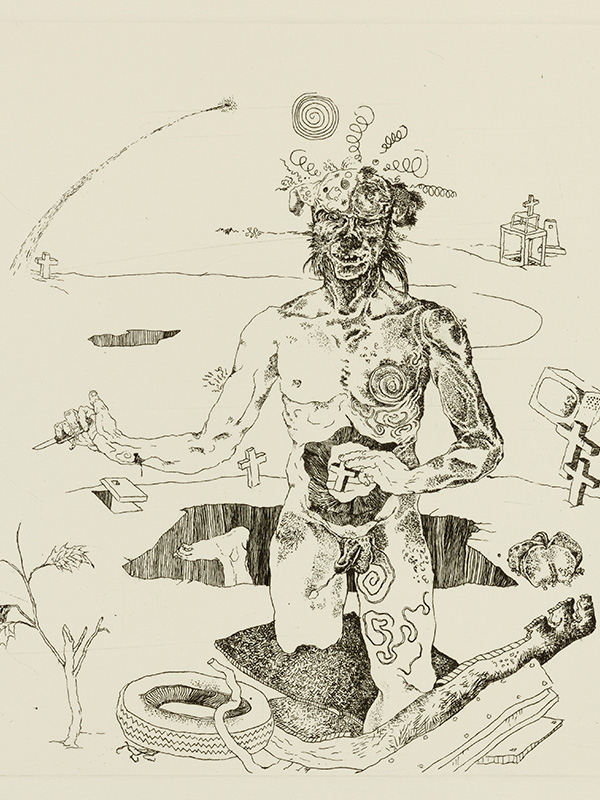

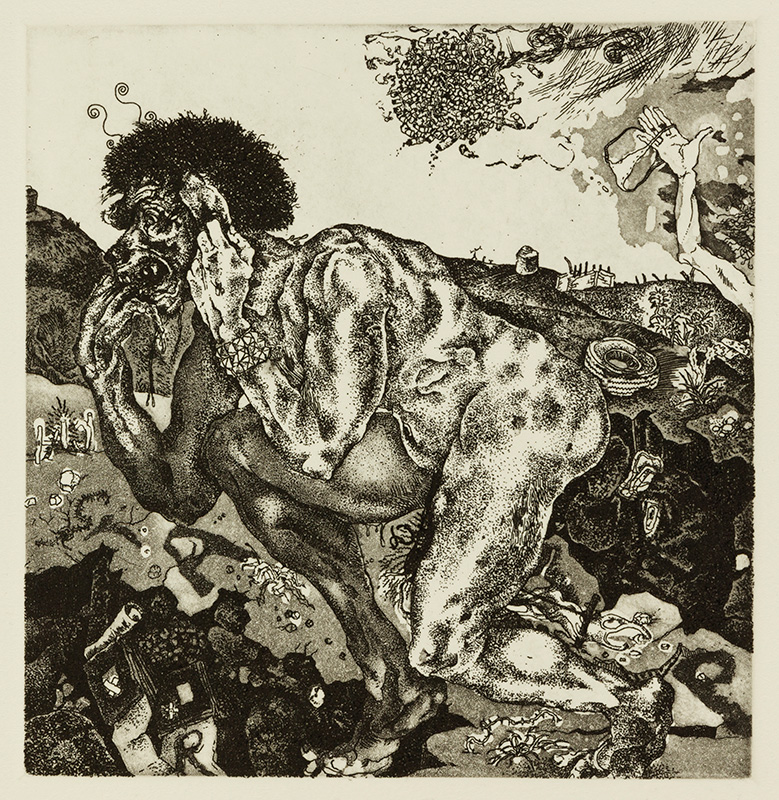

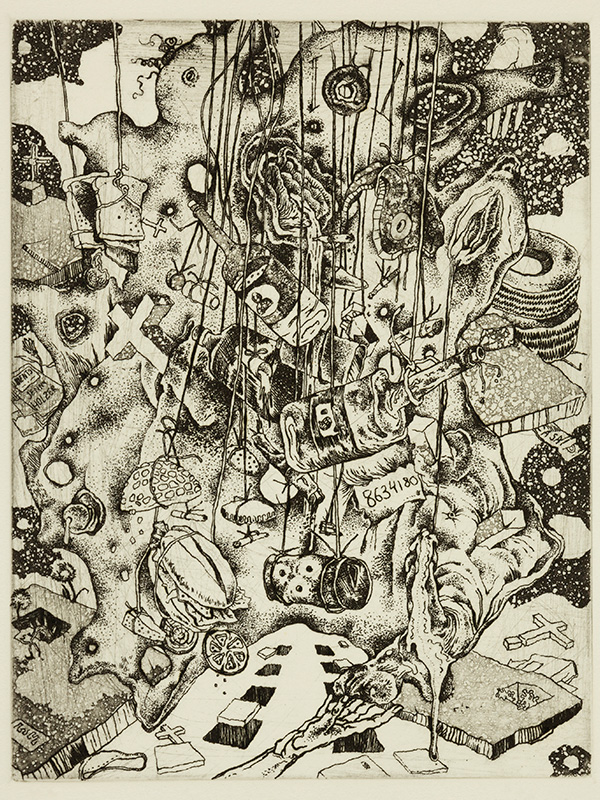

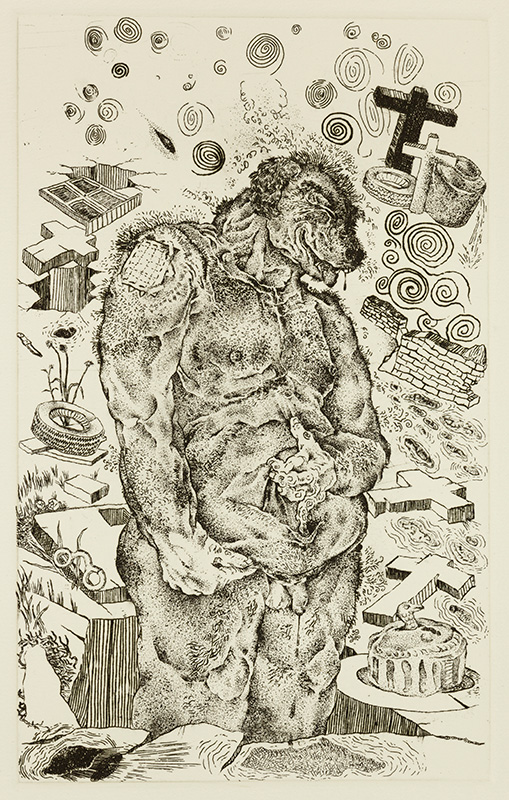

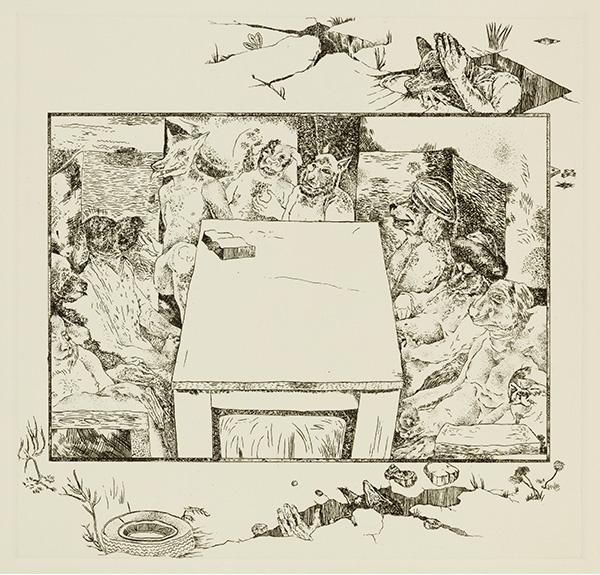

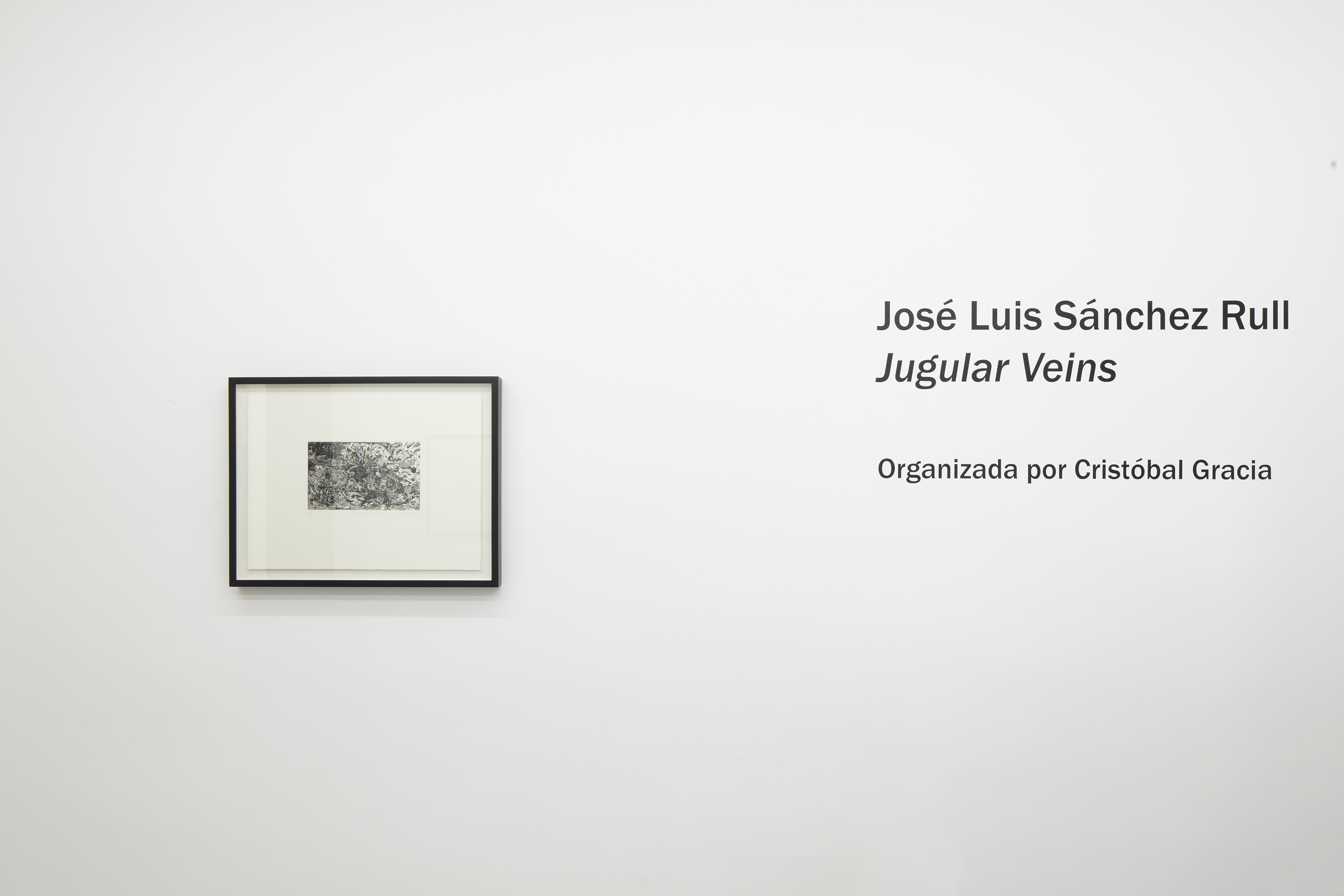

La Suite San Loco, a series of twenty-two etchings signed in 1999, announced the end of the twentieth century and the dawn of the twenty-first. Faced with the disappointment of a failed digital apocalypse, today that ending serves us as a beginning for this exhibition. We might describe these prints as a comic strip of anthropomorphic dogs entering and exiting excavated graves — a story of redemption. Or perhaps of death and transfiguration: a tale crossed by pain, madness, eroticism, passion, and tears, to finally reach forgiveness granted by ourselves, without the intermediation of any god. A transfiguration that does not result in a messiah, nor in a living corpse or a phoenix, but in accepting our own portrait with all its masks and deformities — a beauty that is also horrendous — a series of autoretretes (autoretretes presents a wordplay in Spanish, self-portrait translates as autoretrato while retrete means toilet. In this case an autoretrete could be understood as a self-portrait produced not by the use of a mirror but of a toilet as a mirroring tool to see our own face).

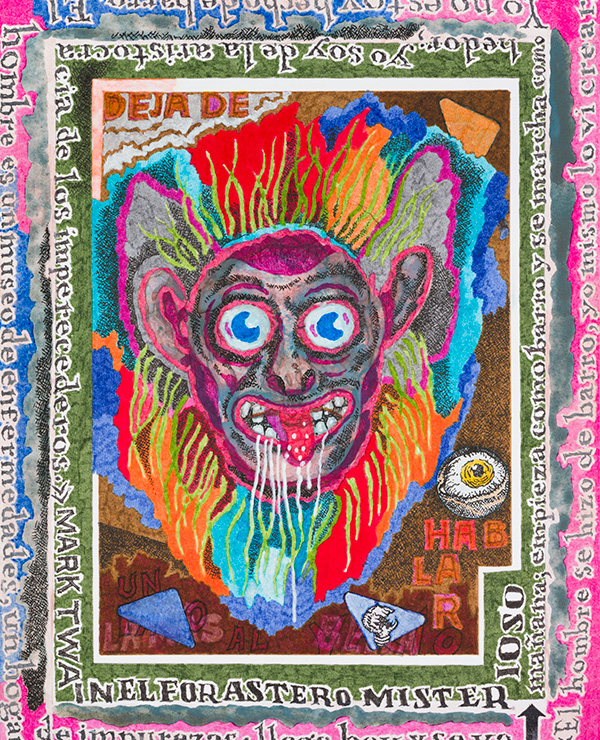

The prints of La Suite San Loco are based on the walks Rull used to take with his dogs in the San Lorenzo Tezonco Cemetery — a burial ground, which at the time was confused with a dump, a place where all dead things end up; almost like an archaeological site in constant fluctuation. It wouldn’t be wrong to imagine that perhaps it was here where the artist found traces of his own antiquity, remnants of his childhood: toy-trash such as the Nutty Mads, monochromatic plastic figures manufactured in the United States between 1963 and 1964. These are usually described as comically grotesque creatures, meticulously detailed and perhaps inspired by characters like Rat Fink. Maybe the Nutty Mad Rull found in that looted tomb (turned trash bin) was The Thinker, a parody of its namesake by Rodin. Yet the Nutty Mad Thinker, rather than posing in deep contemplation with his hand upon his chin, seems closer to Ugolino and His Sons, the marble sculpture by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux from 1860. The intense expression of the plastic figure, hand shoved into mouth, is the point of encounter with Count Ugolino della Gherardesca. Dante’s Inferno tells how this count and his sons were imprisoned and left to starve; in the sculpture, the children offer their own bodies as food to their father. Ugolino, tormented, wavers between sanity and the bestial seduction of cannibalism. The style of the sculpture shows Michelangelo’s influence and echoes of Laocoön and His Sons. It is worth remembering that The Thinker was initially titled The Poet, representing Dante Alighieri, conceived as part of The Gates of Hell. This poses a fundamental question: in which circle of hell does the plastic toy reside?

Historically, the Academy of Fine Arts used classical sculptures as ideal models of beauty, indoctrinating artists to copy this same canon over and over. That repetition and zombie formalism ended up turning these statues into idealized figures emptied of meaning. The homage Rull pays to art history does not arise from indoctrination, much less from an established canon, but from cannibalism — from a conflicted divorce with tradition.

The original molds of the Nutty Mads arrived in Mexico in the 1970s, creating new versions that are generally less appreciated than their gringo counterparts. It’s often said there are undesirable variations in color, or that their careless production process altered the figures. Such dismissive comments usually come from U.S. collectors. Yet once the molds reached our country, they stopped functioning as mechanisms of exact reproduction and instead became a digestive system — one that chews, metabolizes, spits, vomits, defecates, and ejaculates the perverse twin: the otherness that arrives to unsettle the sterilized control of first-world history.

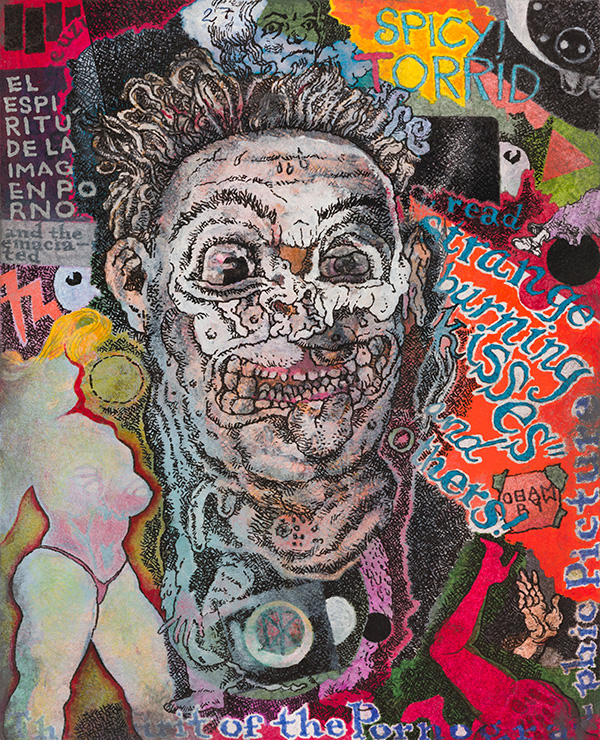

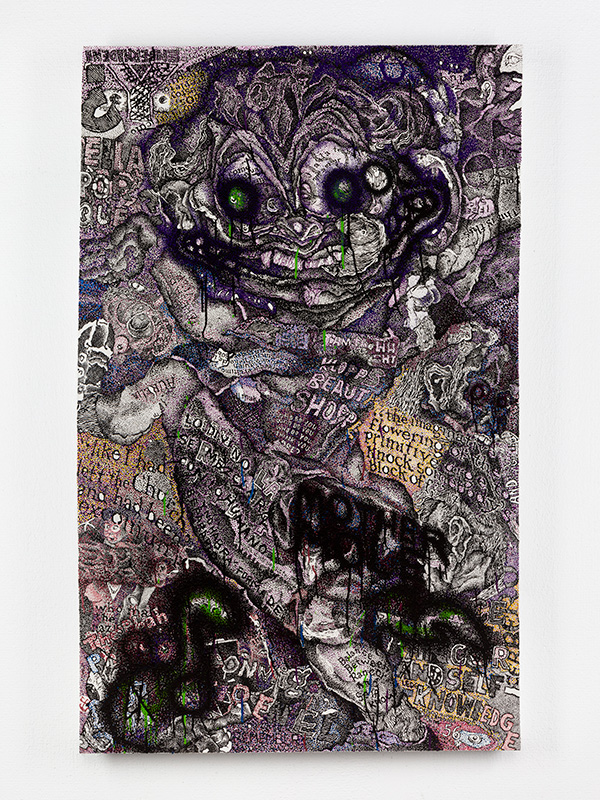

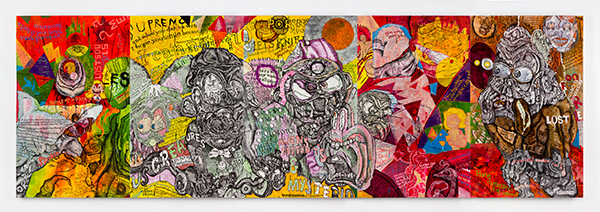

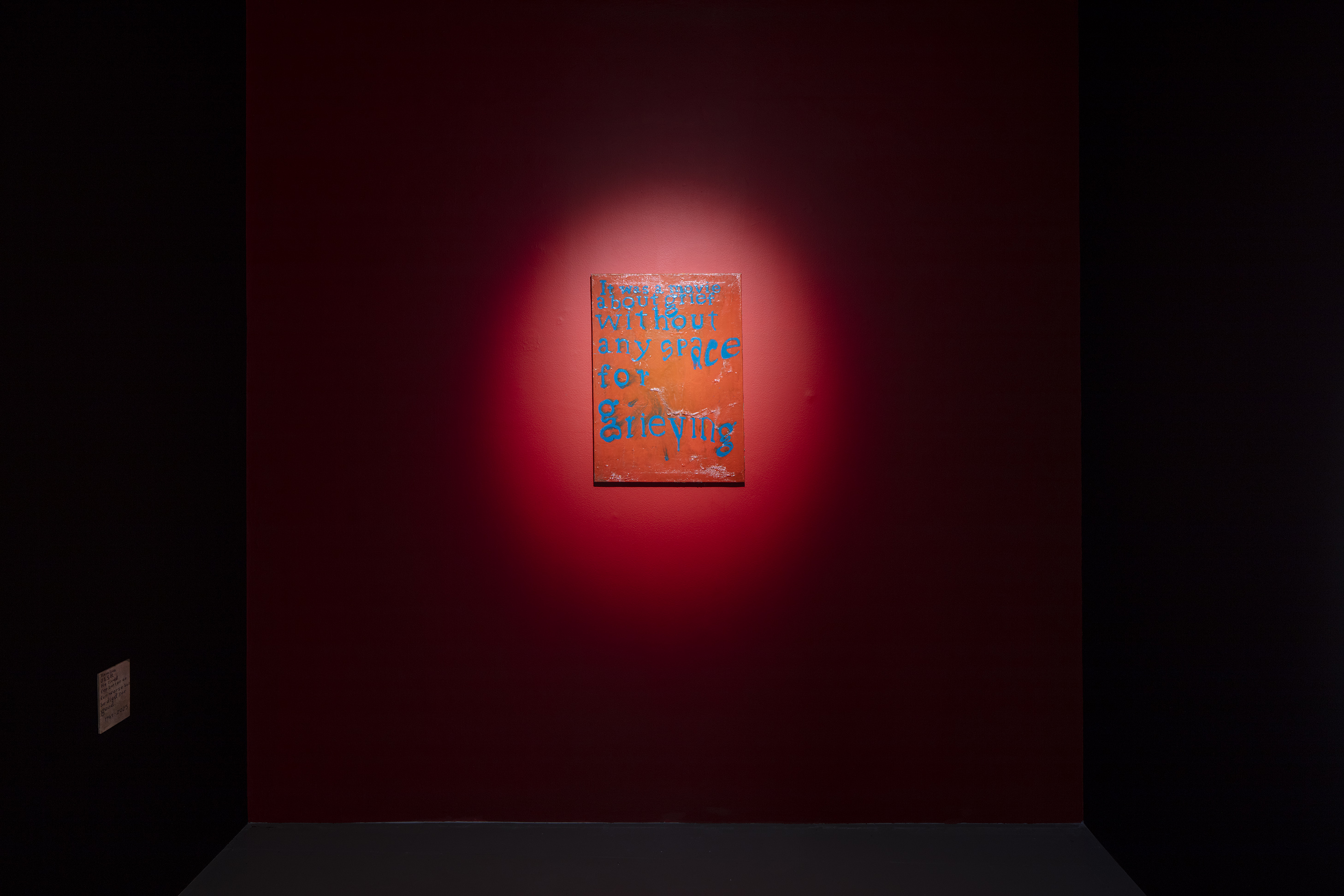

Sánchez Rull uses the Nutty Mads (among hundreds of visual and textual references) as desacralized models — offspring of the plastic burr of popular culture. In his paintings he seeks, in his own words, “to imbue the idiot monster with spirit,” these plastic trinkets being that empty monster which is flooded with meaning until it becomes pure mythology — the jugular vein that carries blood from brain to heart.

These works stem from the search for painting’s zero degree — the preparatory drawing hidden beneath layer after layer of paint. To achieve this, Rull enters into a Xipe-like dialogue with the masters of painting: from Goya to Uccello, from Hans Hofmann to Guston, from Clemente Orozco to Max Beckmann. He begins to flay the GREAT tradition of painting, peeling away its surface. It is not a Greenbergian surface, but a surface as skin — like the book that appears in the horror-comedy movie Evil Dead (1981), the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis, a tome of prophecies and resurrections bound in the flayed head of a demon. It is not hard to imagine the artist in his studio, working while wearing the skin of one of his reference painters as a cloak.

It is essential to understand Rull’s practice as a way of creating the myths under which we want to live, rather than those under which we are obliged to exist. As he begins to flay and erase these layers of paint, a washed-out Velázquez begins to turn into a Rothko, whose Apollonian curtain is torn away to reveal its Dionysian underside. And in the end, instead of finding the drawing traces akin to Dürer’s Salvator Mundi, what happens is what always happens — we find something different from what we sought. Master Sánchez Rull found a Robert Crumb dragged and photocopied through history. This deformation of the Xerox destroys the perfect dot grid of Lichtenstein’s pop art to reveal an anamorphosis, a Rorschach blot where one can see at once a Black Flag flyer designed by Raymond Pettibon and a Motherwell painting. A jumble of art history — a historical memory more than an ideologized present — where the Brillo Box original is Paul Thek’s. Within it are already contained Warhol, Donald Judd, and the soapy product, just as the Nutty Mad Thinker contains Rodin, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Michelangelo, Agesander, Polydorus and Athenodorus of Rhodes, and all of low popular culture.

The gallery’s penumbra lets all these echoes and more be heard, since, like every voice, one’s own is composed of many others. We are all our alter egos (fig. 9-13).

“Satire and parody work only when you reveal a fundamental flaw or untruth in your subject.”

Dan Nadel, Chapter 2, Jugular Veins, Crumb, a cartoonist’s life, 2025

-Cristóbal Gracia.

*Sigmund Freud, The “Uncanny”, 1919